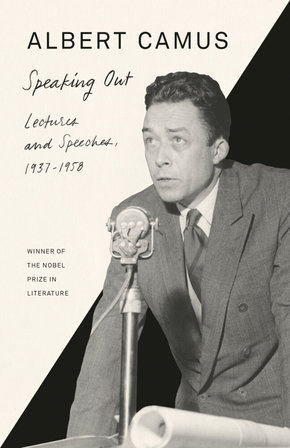

Speaking Out - Lectures and Speeches, 1937-1958

| Verlag | Penguin Random House |

| Auflage | 2022 |

| Seiten | 288 |

| Format | 13,1 x 20,2 x 2,1 cm |

| Gewicht | 288 g |

| Artikeltyp | Englisches Buch |

| EAN | 9780525567233 |

| Bestell-Nr | 52556723EA |

The Nobel Prize winner's most influential and enduring lectures and speeches, newly translated by Quintin Hoare, in what is the first English language publication of this collection.

Albert Camus (1913-1960) is unsurpassed among writers for a body of work that animates the wonder and absurdity of existence. Speaking Out: Lectures and Speeches, 1938-1958 brings together, for the first time, thirty-four public statements from across Camus's career that reveal his radical commitment to justice around the world and his role as a public intellectual.

From his 1946 lecture at Columbia University about humanity's moral decline, his 1951 BBC broadcast commenting on Britain's general election, and his strident appeal during the Algerian conflict for a civilian truce between Algeria and France, to his speeches on Dostoevsky and Don Quixote, this crucial new collection reflects the scope of Camus's political and cultural influence.

Leseprobe:

The Crisis of Man

1946

In spring 1946 Albert Camus was invited by the foreign ministry s French cultural relations department to give a series of lectures in North America. During the sea crossing, he drafted The Crisis of Man, which he read out in French in public for the first time on March 28, 1946, at an evening event at Columbia University, New York, addressed also by Vercors ( Jean Bruller) and Thimerais (Léon Motchane). Camus gave this lecture again throughout his visit to the United States, in a slightly expanded version, the typescript of which was discovered recently in the archives of Dorothy Norman (Beinecke Library, Yale University). This is the version reproduced in translation here. The chief editor of the journal Twice a Year, Norman published The Crisis of Man at the end of 1946, in a translation by Lionel Abel.

Ladies and gentlemen,

When it was suggested to me that I should give some lectures in the United States of Ame rica, I had scruples and hesitated. I am not the right age for giving lectures, and feel more at ease in reflection than categorical assertion, because I do not claim to possess what is generally called truth. When I expressed my scruples, I was told very politely that the important thing was not for me to have any personal opinion. The important thing was for me to be able to pro- vide those few elements of information about France which would allow my audience to form their own opinion. Whereupon I was advised to inform my listeners about the current state of French theater, literature and even philosophy. I replied that it would perhaps be just as interesting to speak about the extraordinary efforts of French railwaymen, or about how miners in the Nord are now working. It was pointed out to me very pertinently that one should never strain one s talent, and that it was right for special interests to be addressed by people competent to do so. With a long-standing interest in lite rary matters while I certainly knew nothing about shunting, it was natural that I should be told to talk about literature rather than about railways.

At once I was enlightened. The important thing in fact was to talk about what I knew, and to give some idea of France. This is exactly why I have chosen precisely to speak neither about literature nor about theater. For literature, theater, philosophy, intellectual study and the efforts of an entire people are merely the reflections of a fundamental interrogation, a struggle for life and man, which constitute for us the whole problem of today. The French feel that man is still threatened, and they feel too that they will not be able to go on living if a certain idea of man is not rescued from the crisis with which our world is wrestling. And that is why, out of loyalty to my country, I have chosen to speak about the crisis of man. And as the idea was to talk about what I knew, I thought I could not do better than to retrace a s clearly as possible the spiritual experience of men of my generation, since that experience has covered the full extent of the world crisis, and can shed some dim light both upon absurd fate and upon one aspect of today s French sensibility.

I should first like to situate this generation. Men of my age in France and in Europe were born just before or during the first great war, reached adolescence at the time of the world economic cri- sis and were twenty in the year when Hitler came to power. To complete their education, they were then offered the war in Spain, Munich, the 1939 war, defeat and four years of occupation and clandestine struggle. So I suppose it is what people call an interest- ing generation, which is why I was right to think it will be more instructive for you if I speak not in my own name, but in that of a certain number of Frenchmen who are thirty today, and whose int