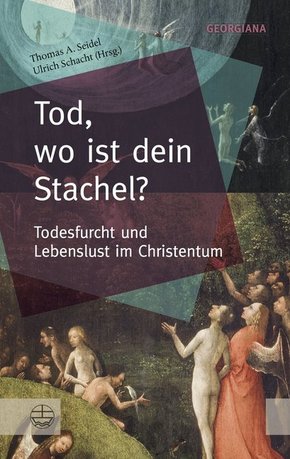

Tod, wo ist dein Stachel? - Todesfurcht und Lebenslust im Christentum

| Verlag | Evangelische Verlagsanstalt |

| Auflage | 2017 |

| Seiten | 280 |

| Format | 12,3 x 19,1 x 2,0 cm |

| Geklebt | |

| Gewicht | 304 g |

| Reihe | GEORGIANA 2 |

| ISBN-10 | 3374050034 |

| ISBN-13 | 9783374050031 |

| Bestell-Nr | 37405003A |

Niemand kann ihm entkommen, dem großen Gleichmacher Tod. »Leben ist gefährlich. Wer lebt, stirbt«, schrieb der polnische Aphoristiker Stanislaw Jerzy Lec mit schwarzem Humor. »Tod ist ... je der meine«, pointierte Martin Heidegger diese situative Radikalität. Und für den Literaturnobelpreisträger Elias Canetti war der Tod ähnlich wie für sein Vorbild Johann Wolfgang Goethe nichts als ein Hassobjekt. In auffälligem Kontrast dazu bekennt das Christentum mit dem Apostel Paulus: »Der Tod ist verschlungen in den Sieg. Tod, wo ist dein Stachel? Hölle, wo ist dein Sieg?« (1. Korintherbrief 15,55) Das meint mehr als nur die sokratische Unsterblichkeit der Seele, wie Platon sie im Phaidon entfaltet. Nach Christoph Markschies waren es nicht zuletzt die intensive Seelsorge an den trauernden Schwestern und Brüdern und die Erwartung der Auferstehung, die die schmerzhafte Endgültigkeit des irdischen Lebens keineswegs leugneten und doch durch heitere Gelassenheit dem Tod gegenüber den frühen Chr istengemeinden rasch Anhänger bescherten.Das anregende, auch existenziell spannende Buch fragt danach, wie der »in den Tod verschlungene« Sieg Christi heute theologisch zu interpretieren ist, angesichts eines exzessiven Materialismus, für den der Tod das möglichst zu verdrängende kalte Schlusswort ist.Mit Essays, praktischen Erfahrungsberichten und literarischen Fundstücken von George Alexander Albrecht, Michael Dorsch, Siegmar Faust, Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz, Frank Hiddemann, Sebastian Kleinschmidt, Dieter Koch, Christian Lehnert, Martin Luther, Ulrich Schacht, Christine Schirrmacher, Cornelia Seidel, Thomas A. Seidel , Peter Zimmerlind.[O Death, Where is Your Sting? Fear of Death and Love of Life in Christianity]Nobody can escape him, the great leveller, Death. »Life is dangerous. Who lives, dies«, wrote the Polish aphorist Stanislaw Jerzy Lec with black humour. And for Elias Canetti as for Johann Wolfgang von Goethe death was nothing but an object of hate. But in marked con trast to that, Christianity with Paul confesses: »Death is swallowed up in victory. O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?« (1. Corinthians 15:54-55).This means more than the Socratic immortality as developed by Platon in his Phaidon. According to Christoph Markschies it was not least the intense pastoral care for mourning sisters and brothers and the expectation of the resurrection, denying in no way the painful finality of earthly life, which because of its cheerful serenity contributed to the rapid growth of the early Christian communities.This stimulating book asks how the victory of Christ, swallowing up death, is to be interpreted today in view of an excessive materialism that sees death as the cold final word that it tries to repress if possible.

[O Death, Where is Your Sting? Fear of Death and Love of Life in Christianity]

Nobody can escape him, the great leveller, Death. "Life is dangerous. Who lives, dies", wrote the Polish aphorist Stanislaw Jerzy Lec with black humour. And for Elias Canetti as for Johann Wolfgang von Goethe death was nothing but an object of hate. But in marked contrast to that, Christianity with Paul confesses: "Death is swallowed up in victory. O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?" (1. Corinthians 15:54-55).

This means more than the Socratic immortality as developed by Platon in his Phaidon. According to Christoph Markschies it was not least the intense pastoral care for mourning sisters and brothers and the expectation of the resurrection, denying in no way the painful finality of earthly life, which because of its cheerful serenity contributed to the rapid growth of the early Christian communities.

This stimulating book asks how the victory of Christ, swallowing u p death, is to be interpreted today in view of an excessive materialism that sees death as the cold final word that it tries to repress if possible.